St Andrew’s Church, accessed by a long track from the hamlet of Sempringham, feels now like a remote outpost of times past, hinting at a rich history which remains just below the windswept farmland of the fens.

Today, visitors to the beautiful church find it surrounded by expansive fields, but 900 years ago it was at the heart of a prosperous village, and the birthplace of the only wholly English monastic order of the medieval age, and its founder – St Gilbert of Sempringham.

The story of Sempringham Priory begins in the years following the Battle of Hastings, as the lands of the Saxon lords were carved up and gifted by William the Conqueror to the new Norman aristocracy.

Albert of Lincoln was granted the estate of Sempringham, and a wealthy knight called Joeclin, was installed as its keeper.

Joeclin married a local woman, possibly the daughter of a previous Saxon landowner.

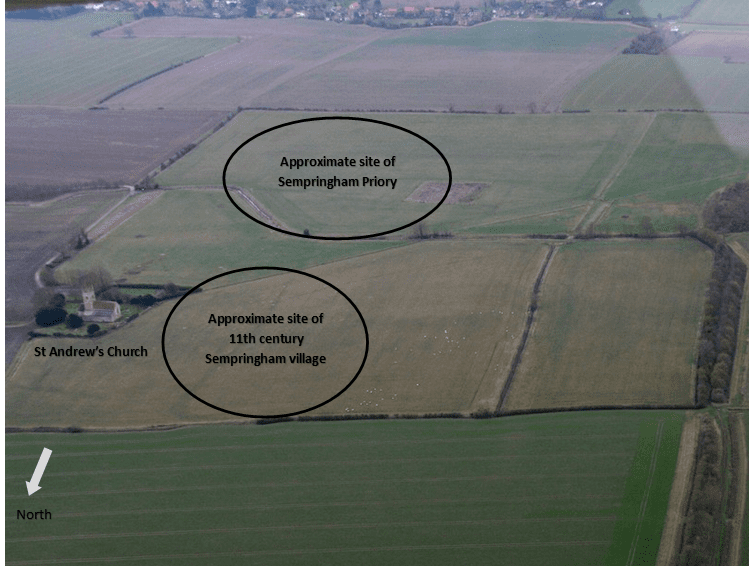

Sempringham Church of St. Andrew and Gilbertine Priory site: aerial 2019 by Chris: Creative Commons license: CC BY-SA 2.0

Accounts vary, but sometime between 1083 and 1086, his wife gave birth to a son – Gilbert. It is said that in the days leading up to the birth she had a vision of the moon descending from the night skies to settle in her lap. She believed this to be a sign her child would be special.

Gilbert was born with a disability, possibly the result of a deformity of his spine – without which Sempringham Priory may never have been built. Instead of training as a knight, as his father had before him, he was sent to Normandy to study for a religious life.

He returned to Sempringham in his late teens, an exceptionally pious young man, and an advocate for education.

Using income from his two parishes, Sempringham, and West Torrington (near Market Rason), he established a school teaching literacy and religion to the children from his father’s estates. Radically for the time, he taught girls as well as boys.

Despite his religious dedication, it was not until he was nearly 40, while he was while working as a clerk to the Bishop of Lincoln, that he became ordained as a priest.

To Gilbert, known for his rejection of luxury, life within the Bishop’s court may have seemed uncomfortably decadent. He shunned promotion to archdeacon, declaring remaining in Lincoln the ‘road to perdition’, and decided instead to return to Sempringham, and a simple life as rector.

After inheriting his father’s estates in 1131, Gilbert dedicated his new income to the establishment of a religious community – a convent, which he built against the north wall of St Andrew’s Church, for seven maidens of the parish. The young women made vows of chastity, humility, obedience, and charity, and lived according to the Benedictine Rule.

Illustration of a Gilbertine nun, from ‘English Monastic Life’ by Abbot Gasquet (1904), Public Domain.

Like most medieval nuns, they lived almost entirely cloistered lives. Their only contact with the outside world was through a window where they would be brought food and clothing, and on occasion, gossip, by women from the village. Local men were employed to carry out manual labour.

Eventually Gilbert offered these servants the opportunity to become lay sisters and lay brothers of the order. They took vows and wore religious habits, but lived under a slightly less restrictive monastic rule; as part of the community, but with more interactions outside of it.

Lay sisters attended the sick and carried out domestic duties such as cooking, brewing, weaving and making clothing for the nuns. Lay brothers were responsible for maintaining property and working on the monastic farms (known as granges) producing food and income – largely through the sale of wool.

Today, it is hard to think of space around St Andrew’s being limited. However, just eight years after its construction the religious community at outgrew the convent site, hemmed in by the church, and surrounded by the village.

Gilbert was gifted the neighboring land, just beyond the modern course of Marse Dike. There he built an extensive priory complex, centered around a new church – St Mary’s. Known as a double house, as it accommodated both men and women who lived in strict segregation.

Sempringham Church of St. Andrew and Gilbertine Priory site: aerial 2019 (2) by Chris Creative Commons licence: CC BY-SA 2.0

The priory church was spilt by a wall separating male and female occupants. To the south of the church the nun’s cloisters, chapter house, and auxiliary buildings, such as an infirmary were built. Ranges of buildings to the north included the cannon’s cloisters (home to priests of the order) and a guest house. Large fishponds would have provided meat for the priory, and there is evidence of a tile kiln and even metal working taking place on site.

It is not difficult to see how the priory would slowly come to subsume the village, with the majority of the villagers taking holy orders, becoming lay sisters or brothers, or working to support the running of the priory in other ways, like as tenant farmers of the monastic granges.

Following the establishment of the double house at Sempringham, the order began to grow, and establish houses elsewhere in the country, particularly across Lincolnshire and Yorkshire, all overseen by Gilbert as Master of the order.

In 1147, aged 60, Gilbert undertook an arduous journey back to France in the hopes that the Cistercians would formally accept Sempringham, and the other houses under his guardianship, as part of their order. However, he was denied, largely because of the position held by women -not only as members of the order, but also as owners of the monastic buildings and keepers of the treasury.

Pope Eugene III granted him the right to formerly establish the Gilbertine Order. Despite his successes and advancing age, some of Gilbert’s greatest troubles were yet to come.

In his early 80’s, Gilbert was caught up in the rift between two of his most powerful friends and allies – King Henry II and Thomas Becket. Gilbert was arrested and imprisoned, accused of sending funds to support the exiled Archbishop of Canterbury. Despite refusing to swear an oath denying his involvement he was eventually acquitted by Henry II.

Around 1165, a scandal erupted at a Gilbertine priory in Watton, Yorkshire, when a young nun, who had been forced to join the order as a girl, was found to be pregnant following an affair with a lay brother there.

The nun was imprisoned in isolation, with her hands and feet shackled and fed only bread and water by the other sisters in the house. When the lay brother was found, his punishment came in the form of a vicious, bloody, and likely fatal assault by the nuns.

The stricture of Gilbert’s rules did not lessen with old age, and in 1670 several lay brothers revolted against him travelling to Rome to complain to the pope about failures in Gilbert’s leadership and administration and the harshness of their living conditions, demanding a relaxation of the rule.

Once more Gilbert was acquitted of wrongdoing, but when the lay brothers returned to the order, they had secured an improvement in their conditions, food and clothing.

At 90, with failing health and having lost his eyesight Gilbert resigned his position as Master, and finally took vows as a cannon within the order he dedicated his life to.

He died on the 4th February 1189, aged around 103, and was buried in the church of St Mary, where his shrine was visible to both the men and women of his order.

Sempringham became a place of pilgrimage, and soon miracles of healing were attributed to Gilbert. He was made a Saint in 1201 by Pope Innocent III.

The fortunes of the Gilbertine order and Sempringham itself faltered after Gilbert’s death, however its story was far from over.

In our next post we continue the tale: what became of the now vanished priory and once thriving community surrounding it – and how it became the home to a lost Welsh princess.