The picturesque, adjoined villages of Caythorpe and Frieston lie approximately eight miles north of Grantham on the A607. The villages have been closely linked for centuries and share the parish church of St Vincent’s in Caythorpe.

During the Second World War, the village was a billet for 216 Signals Parachute Squadron, who played a major role in the battle of Arnhem. The Squadron has retained a long association with the village, and St Vincent’s has become a shrine to the Airborne Forces with memorials including beautiful and unique commemorative windows.

Over the next year the fascinating and moving stories of the young men serving with Airborne Forces, and the impact they had on the towns and villages of South Kesteven, will be revealed through the recently launched ‘Soldiers from the Sky’ project, funded by the National Lottery Heritage Fund, UK Shared Prosperity Fund and South Kesteven District Council.

In this blog however, we are looking back over 200 years before 216 Squadron made the village its home, to a time when men looked to the skies not in the pursuit of war, but to predict the future.

In 18th century Frieston, near to the village green, there was a house surrounded by sundials and other scientific instruments. The resident of this curious home was Edmund Weaver (1683-1748), who was born and lived in the village and is buried at Caythorpe Church.

Weaver was an entirely self-taught astronomer and mathematician, who, according to the inscription on his grave marker which can now be found in the Chancel of St Vincent’s , was ‘by his own industry from a low education… justly esteemed as one of the best Astronomers of Ye Age’.

He was close friends with William Stukeley, who described him in an account to the Royal Society, later published in Philosophical Transactions[1] as a ‘very uncommon genius… scarcely to be accounted the second in the Kingdom… an instance of great merit in obscurity.’

High praise indeed from a man who counted Sir Isaac Newton as a friend, famously writing the biography which would forever link the discovery of the laws of gravity to an apple tree at Woolsthorpe Manor.

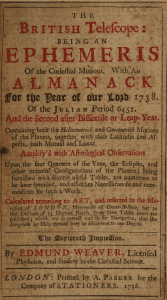

While Stukeley may well have considered Edmund Weaver to have lived in obscurity, there was one regard in which he was well known, as the author and publisher of a famous almanac – ‘The British Telescope’.

The annual publication charted the positions of stars and the phases of the moon – which were used to determine everything from navigation at sea, to when to plant crops, and described and predicted various celestial events such as the transit of Venus and lunar eclipses.

Noted at the time for its accuracy, the almanac was published annually between 1715 and 1749, with the final edition being published the year after his death.

Alongside astronomy the almanac also contained astrology, predicting affairs of state, personal grievances, and chances of promotions as well as the weather through the movements of the stars within the zodiac.

In his edition of 1738, for example, Weaver’s predictions for the Autumnal Quarter warn that:

‘The positions of the celestial harbingers produce untoward wranglings, strife and discord, affronting even Majesty itself’, and that the position of Jupiter, Mercury and Venus ‘denotes lawsuits and controversies with tricking, cozenage and deceit; scurrilous invectives, lying apparitions and the like, together with ecclesiastical dispute’

While the inclusion of astrology in a largely scientific text may seem odd today, at the time what many now consider to be superstition was viewed on and equal basis to the scientific calculation of the transit of stars and would not have seemed at all out of place.

In addition, the almanac also contained useful information of for the year such as the dates of holidays and saints days, as well as items of interest such as the ‘Large Chronology of Remarkable Things’, lists and lineages of English kings, and even reviews of new books.

Examples of Weaver’s almanac have been digitised and made available online through Google Books, and can be found through this link: The British Telescope – Google Books

be found through this link: The British Telescope – Google Books

The tradition of South Kesteven Almanac makers continued when Robert White, a teacher of Mathematics in Grantham, began producing ‘White’s Ephemera’ in 1750.

An account by Henry Andrews[2], a family friend of White’s, and a fellow astronomer, describes him as ‘a lame man, about middling size’ who ‘continued to write Almanacks [sic] until the day of his death’. While his almanacs were not quite as well regarded as Edmund Weaver’s they were still considered to be among the best available at the time.

Henry Andrews’ opinion on almanacs was one to be trusted.

Born in 1744, also in Frieston, he was a neighbour to Edmund Weaver. Andrews began to show a talent for mathematics and astronomy from an early age. Like Weaver he was largely self-taught, and he did not let his humble upbringing limit his achievements. His parents were agricultural labourers, and the little education he did receive was provided while he was in service as a child.

Despite this he is known to have begun his study of the stars as a young boy, even making his own telescope at the age of 10.

He went on to contribute to and edit some of the most famous almanacs of the day, including Old Moore’s Almanac and the Nautical Ephemeris. He was also employed as a calculator for the Board of Longitude, a government body which existed to promote and encourage scientific investigation into solving the problem of finding longitude at sea.

Almanacs were the 18th century equivalent of popular science books, and through many of the almanacs which Henry Andrews worked on contained as much superstition as science, he is credited for introducing a more rigorous logic to the works, and introducing scientific principles to a much wider audience, which included not only gentlemen and scholars, but also working people[3].